WHQR's Sunday Edition is a free weekly newsletter delivered every Sunday morning. You can sign up for Sunday Edition here.

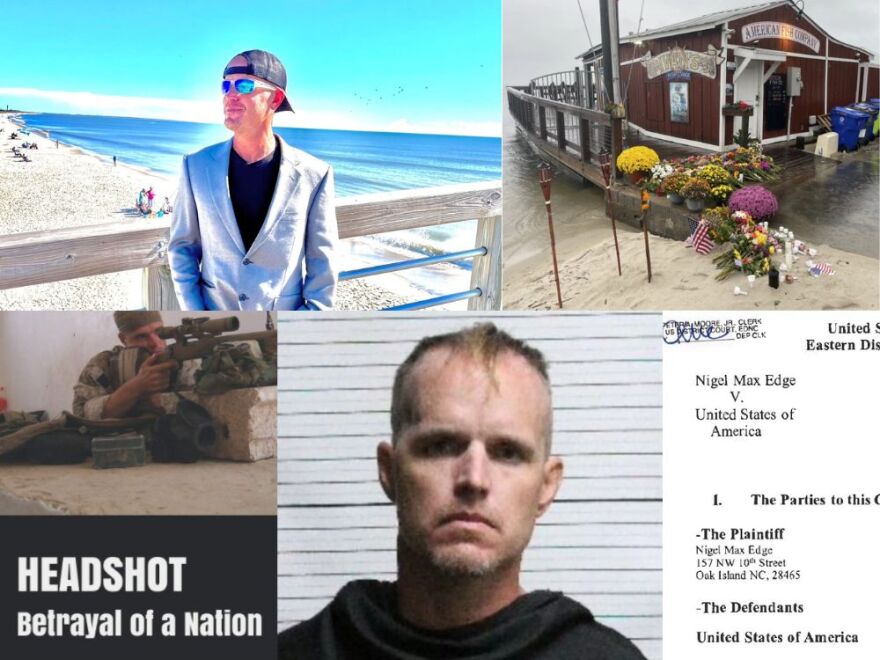

On Sunday morning, as we were reporting out the aftermath of the tragic shooting in Southport, I had a queasy moment of realization: I knew the alleged shooter, Nigel Max Edge, formerly Sean William DeBevoise.

About a year ago, Nigel (as he introduced himself) walked into the WHQR studios with a folder of documents, asking to talk to me. We spent about thirty minutes, maybe longer, going through the files he brought: old newspaper clippings, paperwork from his time serving as a U.S. Marine, and seemingly random documents. The first thing Nigel showed me was a graphic photo of himself, naked and bloodied on an operating table, surrounded by medics, one holding a piece of gauze to a wound on his head.

Nigel wanted me to report on his story, which involved his being a “feral child” who was kidnapped, given a new, false identity, and then trafficked and sexually abused – all part of a massive conspiracy involving Jeffery Epstein, Abu Ghraib, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and “LGBQT White Supremacist Pedophiles.” He implied heavily that his fellow Marines had attempted to assassinate him.

He had linked together the documents in his folder with a series of increasingly incoherent logical jumps; he saw coded messages in newspaper articles, and corroborating evidence in things that seemed unrelated to me.

I could tell he was getting frustrated with me because I was not ‘getting it.’ He rushed through his story, as if he felt there was an invisible clock, like someone who knew he’d only get one shot at explaining himself and only so much time to do it – and, in a way, he was right. I didn’t throw him out, but I definitely tried to steer the conversation towards a conclusion.

This was not the first time I’d sat down with someone who seemed mentally unwell. That comes with the territory as a journalist, and sometimes people can be struggling with mental health, but also telling you the truth about their story. So I always try to hear people out. And, as I’ve done in the past, I tried not to challenge him – I listened to his story, unbelievable though it was, and tried to follow along. I didn't pretend to understand what it must have been like, because there's no way I could. I suggested it might be good for him to have a professional to talk to. I told him, truthfully, that if his story was legit, our newsroom did not have the resources or the reach to cover it. I gave him my card and told him to call me or email if he wanted. As he left, I tried to strike a conciliatory note. I wasn’t going to do the story, but we could keep talking. He was upset and disappointed. He clearly felt like I wasn’t going to help him and, again, he was right.

My conversation with Nigel left me rattled for a few days. For one, the nervous, frustrated energy that vibrated off of him was unsettling. While he was deferential and civil with me, you could tell he was alienated and angry. Not a great combination.

But it shook me up for another reason, too: unlike some people who have told me stories that were completely divorced from reality, Nigel's story was threaded through with real horror.

His discharge and disability papers seemed legit; he had been shot four times in 2006, including a penetrating head wound that left him with a traumatic brain injury. The scars on his body lined up with the injuries in the photo: it was definitely him. Just a few years younger than me, we’d both been young men on 9/11, but while I’d stayed in college, he’d enlisted, gone to Iraq, and been torn to shreds. Despite his horrendous wounds, chronic PTSD, and the prognosis that he’d never walk again, he got back on his feet, literally and figuratively, pursuing both a career and his education. He’d even had a brush with fame, as Kellie Pickler’s date (along with his service dog, Rusty), attending the CMT music awards.

But something had gone wrong, shortly before the pandemic, it seems. I’ve heard there were people who tried to help Nigel. I’m sure the isolation of the pandemic didn’t help. I later learned he’d written a book, hinting at some of the conspiratorial ideas that became more pronounced in his federal lawsuit against the United States, filed right around the same time he came to see me.

He told me there was no one in his life who could or would help him. I asked about the VA; he shook his head, made a quiet, bitter, laughing noise.

“No one cares,” Nigel told me. In a way, he was talking about his conspiracy theory story – but in another way, he was talking about something all too real and all too common.

That part of the story is true – I know, not just because of the documents, but because of the dozens of other veterans I’ve met with similar stories. They’re not delusional or dangerous. They’re just people who have sometimes seen, endured, even committed horrible acts of violence – on behalf of the American people – only to come home to find there’s no place for them.

I don’t claim to have any special insight into Nigel’s life or state of mind. He didn’t seem violent, and while there was a great deal of violence in his story, he never suggested he wanted to take violent action. If Nigel is guilty of this weekend’s terrifying shooting attack, I don’t know what happened to make him do it. Again, these are allegations, and he deserves his day in court – which could take months or years.

I’ve thought a lot about whether – and how – to talk about this, and whether it would be in any way useful to the conversation going on right now. None of it can possibly ease the anguish of the victims’ loved ones, and I doubt it’s any consolation for the people of Southport, and the greater Cape Fear region, who have been rocked by the shootings on Saturday night.

We can, and should, have debates about guns and mental health, in the wake of this shooting – although, depressingly, sometimes that just feels like an empty ritual, performed after every shooting.

But I hope there remains room in the discourse for a specific conversation about veterans. Because we’re failing them, by the thousands. Most suffer in silence, but once you hear it, it's hard to forget.