A quaint farmhouse with black shutters in Surry County now stands empty. Mary Marshall cleans off the kitchen countertops and stages the room for potential buyers.

“I think that table and chairs look good there and we probably need to leave it," she tells her husband Terry. "They look so pretty and we don't need it any more.”

The Marshalls have lived in their home for the past 30 years. It's full of memories. But ever since large chicken houses have encroached on their property, it's become a nightmare.

RELATED: Neighbors Lobby For More Regulation On Chicken Farms

“Our kids were raised here and we fully expected our daughter to get married in the back yard,” Mary says. “Well, there's no way we can make a plan like that because you don't know when the odor is going to come. You can't live like that.”

The Marshalls reached deep into their retirement to buy a new house nearby. It's a hard decision and a financial burden, but they say it will save their marriage and their health. Mary has breathing problems when the odor is strong and she thinks they're caused by the waste from these large chicken houses.

“I also feel so let down by the people in the community because we have been told we've been dividing the community because we dare to complain about it,” she says. “And when somebody tells you, you need to back down because a man's got to make a living, but what about my right to enjoy my property and my land?”

“We don't want to do anything to harm a neighbor, or harm ourselves or our kids, the air or water,” says Johnny Simmons, who comes from a long line of farmers, and runs a chicken operation in Surry County. “We want to preserve it for the future, so we try to do the best job we can realizing [that] to produce the amount of food needed at an affordable price for the company, we have to make sacrifices.”

Simmons says many farmers here have invested money to improve their operations, including building new manure sheds to store the waste.

He says more regulation would devastate the local farming community.

“It's unfortunate that they [those who complain about the farms] feel the way they do, but the farmer, the land there, he's in an agricultural district. His land is zoned by Surry County as agricultural use. He's following the rules and he's following the regulations, so if that's what he wants to do, he's allowed to do so,” says Simmons.

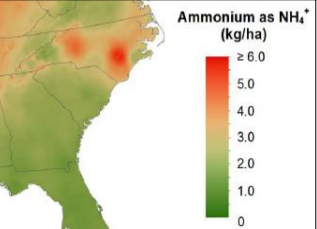

A new report from the NC Department of Environmental Quality says animal livestock waste generates the most ammonia emissions in the state with an estimated 155 tons emitted. A "hot spot" has been identified in the Yadkin River Basin. Courtesy of NC DEQ.

Right now, there's very little regulation of the poultry industry in the state. As WFDD reported Thursday, a new study from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality shows that there is a lot more waste coming from chickens than officials realized, and that because of the lack of oversight, the state doesn't have a handle on where the operations are, how quickly they're expanding, and how they're storing their waste.

But Brian Long with the state Department of Agriculture says there are guidelines for how close farms can be to residential areas, and most small farmers are doing a good job following the rules.

“It's an illustration of how we are a state that is facing some issues of coexistence between farming and growing residential development,” Long says.

In 2015, poultry accounted for more than half of overall farm income in Surry County, a place that's always relied on agriculture, like tobacco. Tomislav Vukina is a professor at North Carolina State University who specializes in the economics of farming, and he says that money is vital to rural counties like Surry.

“If you have the expansion of the poultry industry that comes through the construction of new barns [and] new facilities, then the tax base goes up,” says Vukina. “That means the tax revenue goes up, [and] that means the county can do more things such as fund public schools. So there's no doubt that this is a positive effect.”

RELATED: New State Report Finds ‘A Lot More' Poultry Waste Than Officials Realized

The Marshalls aren't sure they'll be able to sell their house, but they want this experience behind them. Terry Marshall says he's worried that their new home just one county over may not be far enough away from the growing poultry industry.

“We don't know. There's no way of knowing. It's possible they could move in. I hope not. But with the way the rules and regulations stand right now they can build them any place, any place at all,” says Terry. “There's nothing to stop them or slow them down. I don't know if any one of us are safe.”

For now, the Marshalls say they're looking forward to things like cooking on the grill, opening their windows and gardening outside their new home – something they haven't been able to do in a long time.

*Follow WFDD''s Keri Brown on Twitter @kerib_news

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad